Washington, DC - It’s a fetching frock with spaghetti straps, an engineered paisley print, and an asymmetrical hemline. And it’s at the center of a law enforcement action against department store chain Lord & Taylor for its allegedly deceptive use of native advertising – the first case of its kind since the FTC released its Enforcement Policy Statement in December. The lawsuit also challenges Lord & Taylor’s “product bomb” campaign on Instagram as misleading.

Lord & Taylor used an extensive social media push to launch Design Lab, its own apparel line aimed at women between 18 and 35. The strategy was interesting: Focus on just one item – that paisley asymmetrical dress.

Lord & Taylor used an extensive social media push to launch Design Lab, its own apparel line aimed at women between 18 and 35. The strategy was interesting: Focus on just one item – that paisley asymmetrical dress.

For the native advertising part of the campaign, Lord & Taylor signed a contract to have Nylon, an online fashion magazine, run an article about the Design Lab collection featuring a photo of the paisley dress. Lord & Taylor reviewed and approved the paid-for Nylon article, but didn’t require a disclosure about their commercial arrangement.

In addition, Lord & Taylor contracted to have Nylon post a photo of the paisley dress on Nylon’s Instagram page. Again, Lord & Taylor reviewed and approved the paid-for post, but didn’t require a disclosure.

That was only part of the campaign. Lord & Taylor also recruited a team of fashion influencers, all of whom had two things in common: a sense of style and a massive number of followers on social media platforms.

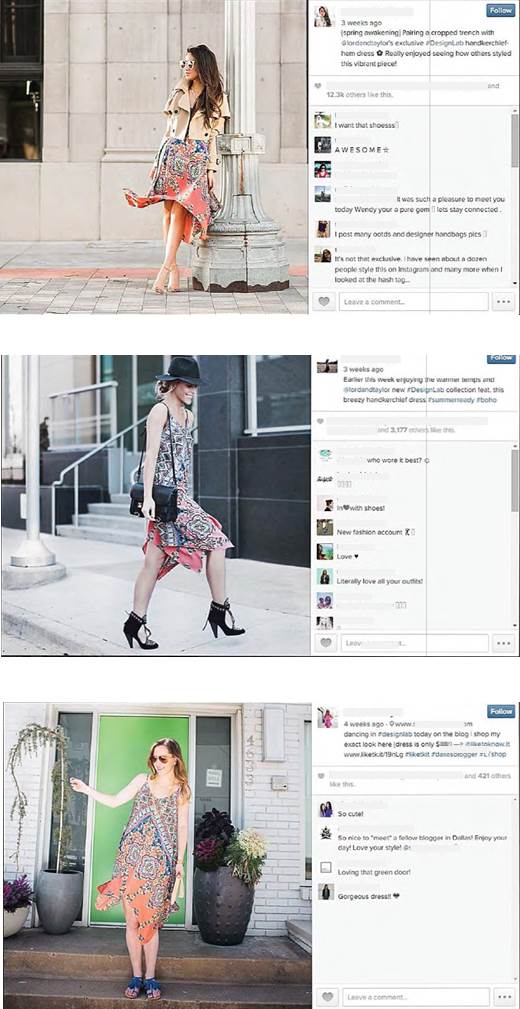

Lord & Taylor gave the dress to 50 influencers and paid them between $1,000 and $4,000 to post photos of themselves in the dress on Instagram on one specified “product bomb” weekend in March 2015 – the same weekend when Nylon posted its Lord & Taylor-approved photo. Style the dress any way you like, Lord & Taylor told the influencers, but in other aspects, the contract was all business. The influencers had to: 1) use the @lordandtaylor Instagram user designation and the campaign hashtag #DesignLab in the photo caption; and 2) tag the photo @lordandtaylor.

Lord & Taylor’s reps preapproved each of the influencers’ Instagram posts to make sure they included the required hashtag and Instagram designation. The company also edited some of what the influencers planned to say.

But despite the company’s punctilious approach to hashtags, handles, and the like, Lord & Taylor was curiously silent about other key aspects of the campaign. For example, according to the FTC, Lord & Taylor’s contract didn’t require the influencers to disclose that Lord & Taylor had paid them. Furthermore, none of the Instagram posts Lord & Taylor approved included a disclosure that the influencer had received the dress for free, that she had been compensated for the post, or that the post was a part of a Lord & Taylor ad campaign. And as the complaint alleges, Lord & Taylor didn’t add a disclosure to that effect to any of the influencers’ posts it reviewed.

But despite the company’s punctilious approach to hashtags, handles, and the like, Lord & Taylor was curiously silent about other key aspects of the campaign. For example, according to the FTC, Lord & Taylor’s contract didn’t require the influencers to disclose that Lord & Taylor had paid them. Furthermore, none of the Instagram posts Lord & Taylor approved included a disclosure that the influencer had received the dress for free, that she had been compensated for the post, or that the post was a part of a Lord & Taylor ad campaign. And as the complaint alleges, Lord & Taylor didn’t add a disclosure to that effect to any of the influencers’ posts it reviewed.

The Instagram campaign reached 11.4 million individual users, resulting in 328,000 brand engagements – likes, comments, reposts, etc. – with Lord & Taylor’s Instagram handle. And the paisley dress sold out.

The FTC complaint charges Lord & Taylor with three separate violations: 1) that Lord & Taylor falsely represented that the 50 Instagram images and captions reflected the independent statements of impartial fashion influencers, when they really were part of a Lord & Taylor ad campaign to promote sales of its new line; 2) that Lord & Taylor failed to disclose that the influencers were the company’s paid endorsers – a connection that would have been material to consumers; and 3) that Lord & Taylor falsely represented that the Nylon article and Instagram post reflected Nylon’s independent opinion about the Design Lab line, when they were really paid ads.

Under the terms of the proposed settlement, Lord & Taylor can’t falsely claim – expressly or by implication – that an endorser is an independent user or ordinary consumer. If there is a material connection between the company and an endorser, Lord & Taylor must clearly disclose it “in close proximity” to the claim. And Lord & Taylor can’t suggest or imply that a paid ad is a statement or opinion from an independent or objective publisher or source. You can file an online comment about the proposed settlement by the April 14, 2016.

What does the Lord & Taylor case suggest for your company’s social media campaigns?

If you use native advertising, consider the context. As the FTC explained in Native Advertising: A Guide for Businesses, “The watchword is transparency. An advertisement or promotional message shouldn’t suggest or imply to consumers that it’s anything other than an ad.” Review your native ads from the perspective of consumers who don’t have your industry expertise about new forms of promotion.

If there is a material connection between your company and an endorser, disclose it. What’s a material connection? According to the FTC’s Endorsement Guides, it’s a connection between the endorser and the seller that might materially affect the weight or credibility a consumer gives the endorsement. Read The FTC’s Endorsement Guides: What People Are Asking for nuts-and-bolts compliance advice and apply those principles if you enlist influencers, bloggers, or others in your marketing efforts.

Disclosures of material connection must be clear and conspicuous. What about explaining a material connection in a footnote, behind an obscure hyperlink, or in a general ABOUT ME or INFORMATION page? No, no, and no. As with any disclosure of material information, businesses should put the disclosure in a location where consumers will see it and read it. The terms of the Lord & Taylor settlement apply just to that company, of course, but for prudent marketers, a good rule of thumb is the standard in that order: “in close proximity” to the claim.

Train your affiliates and monitor what they’re doing on your behalf. If your company uses social media campaigns like this, make your expectations clear at the outset with influencers and follow through with an effective compliance program. There’s no one-size-fits-all approach, but The FTC’s Endorsement Guides: What People Are Asking lists elements every program should include:

- Because advertisers are responsible for substantiating objective product claims, explain to your network the claims you can support;

- Instruct them about their responsibilities for disclosing their connection to you;

- Periodically search to make sure they’re following your instructions; and

- Follow up if you spot questionable practices.