Washington, DC - Advances in payment methods could end those open-wallet debates about who owes what for the pizza. But as innovative technologies change how people pay for things, established consumer protection principles apply. An FTC complaint against peer-to-peer payment service Venmo – now operated by PayPal – alleges that the company failed to disclose material information about the availability of consumers’ funds. In addition, the lawsuit challenges aspects of the company’s privacy and security practices. A proposed settlement in the case requires Venmo to make clear disclosures about certain business practices.

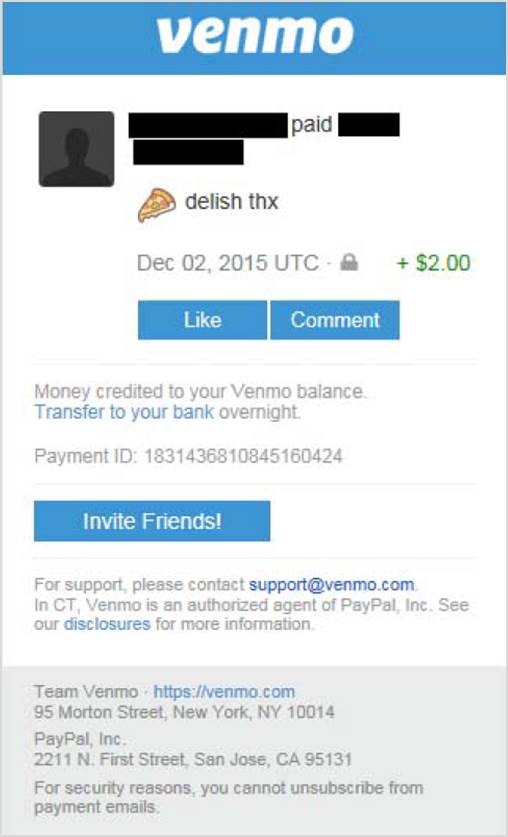

How Venmo works. When consumers download the Venmo app, they create an account connected to their bank account or credit or debit card. They can receive money from other Venmo users, transfer money to them, or transfer some or all of their Venmo balance to their bank account. So let’s say a Venmo user wants to pay another user $10 for that pizza or to get the other person to kick in their $10 share. To initiate a transaction, he or she either sends money to the other user or submits a “charge request” that asks the person to pay. Users must include a short message with each transaction. Within seconds, the recipient gets a notification about the transaction. The language changed over time, but Venmo typically said things like “Money credited to your Venmo balance. Transfer to your bank overnight” or someone “paid $[X] to your Venmo balance [description of transaction.] – Leave it in Venmo or transfer it to your bank account.”

Venmo’s transfer policies. According to the complaint, the company’s representations led many consumers to believe that when they received payment notifications from Venmo, the funds were ready to be transferred to their bank account. But that wasn’t the case. The complaint alleges that in many instances, consumers weren’t able to transfer funds as promised. That’s because Venmo waited until a consumer attempted to transfer funds to his or her external bank account to review the transaction for fraud, insufficient funds, or other problems. For many consumers, once Venmo undertook that review, it resulted in delaying the transfer or even reversing the transaction altogether.

Those delays and losses led thousands of consumers to complain to Venmo. Many people reported that the company’s practices resulted in significant financial hardship – for example, not being able to pay their rent even though it appeared they had enough in their Venmo account to cover it. The complaint alleges that even in the face of mounting consumer complaints, Venmo continued to claim – without any qualifiers – that once money was credited to consumers’ Venmo accounts, users could transfer it to their bank accounts. The FTC alleges that Venmo’s failure to adequately disclose to consumers that funds could be frozen or removed from their accounts was deceptive.

Venmo’s privacy practices. Consumers’ access to funds wasn’t the FTC’s only concern. By default, all peer-to-peer transactions on Venmo are displayed on Venmo’s social news feed. That includes the names of the payer and the recipient, and the accompanying message. In addition, each Venmo user has a profile page that lists their Venmo transactions. By default, their five most recent ones were visible to anyone on that page, including visitors who don’t have a Venmo account. (People without an account could still see a user’s Venmo account either by clicking on a link to the user’s Venmo profile page or by using a search engine.)

Consumers who didn’t want to share their transactions could go to a Venmo menu to edit their privacy settings. By changing the “Default Audience Setting,” people could set the default visibility of their future transactions on the news feed to specific groups, like “Participants Only” or “Friends.” The problem, alleges the FTC, is that setting the Default Audience Setting did not limit how the other party to the transaction could share the transaction. To ensure that their transactions remained at their chosen default visibility, consumers had to take a second inadequately disclosed step involving what was called the “Transaction Sharing Setting.” If people didn’t change both settings, some of their transactions remained visible. The same problem occurred if consumers took action to limit the visibility of a particular transaction, but didn’t change the Transaction Sharing Setting.

Venmo’s data security promises. The FTC also challenged as false a Venmo claim that it protected consumers’ financial information with “bank grade security systems.” According to the complaint, until March 2015, Venmo failed to implement some basic safeguards. For example, Venmo didn’t notify consumers about changes to their settings from within their Venmo account – for example, that their email address or password had been changed. (Notifications like that can alert consumers that an unauthorized person is monkeying with their account.)

Alleged GLB violations. The complaint includes allegations that Venmo violated the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Privacy Rule by failing to provide users with a clear initial privacy notice, by failing to deliver it in a way that each consumer could reasonably be expected to receive it, and by distributing a notice that didn’t accurately reflect its practices. In addition, the FTC says Venmo violated the GLB Safeguards Rule by failing to have a comprehensive written information security program in place before August 2014 and by failing to implement safeguards to protect the security, confidentiality, and integrity of consumer data until at least March 2015.

The proposed order. To settle the case, PayPal (which now owns Venmo) has agreed not to make misrepresentations about material restrictions or limitations on the use of any payment service with a social networking component. The proposed order also requires PayPal, when making representations about the availability of funds to be transferred or withdrawn to a bank account, to clearly disclose that the transaction is subject to review and that funds could be frozen or removed. In addition, PayPal must provide clear disclosures about how any payment and social networking service shares transaction information with other users and must tell consumers how to adjust privacy settings to limit how that information is shared. PayPal also must get every-other-year data security assessments for 10 years.

The FTC is accepting public comments about the proposed settlement until March 29, 2018. In the meantime, prudent businesses can take some tips from the case:

- Be clear about consumers’ payments. When you’re dealing with payments – including when new financial technologies are involved – be clear with consumers about when payments are sent and when they’re actually received. If there are material terms or limitations, disclose them clearly. Transparency is a key to winning consumer confidence.

- Think through your data defaults. Yelling “Surprise!” may be fun at birthdays, but consumers are decidedly less jovial when they’re surprised by how companies use their information. In deciding on your default settings and how to educate consumers about your product, factor in reasonable consumer expectations.

- Keep privacy options accurate. Consumers appreciate choices, but they need to understand what they are choosing. If you provide privacy options, make it straightforward for consumers to select the options that best match their privacy preferences – and then honor their choices.

- Is your company covered by GLB? The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Privacy Rule and Safeguards Rule apply to “financial institutions,” but the law defines that term broadly. The scope of the statute extends beyond businesses with tellers, vaults, and ballpoint pens chained to the table. You need to know if your company is covered by those rules, especially if you’re part of the rapidly growing peer-to-peer payment industry.