San Diego, California - Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego researchers published new findings on the role geological rock formations offshore of Japan played in producing the massive 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake¾one of only two magnitude 9 mega-earthquakes to occur in the last 50 years.

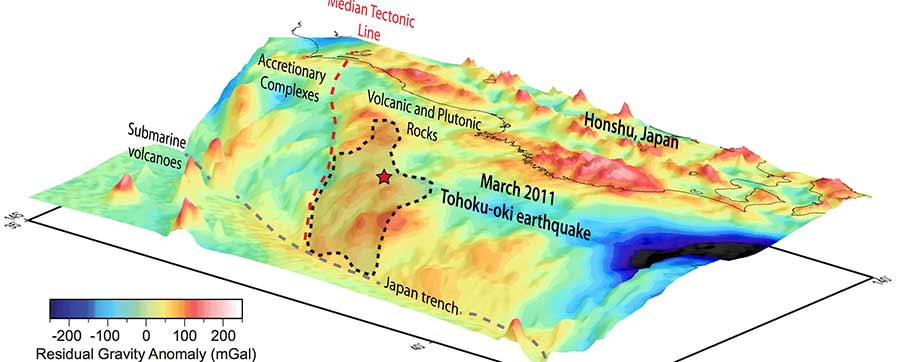

A graphic of gravity data off Japan where the 2011 magnitude 9 earthquake occurred.

The study, published in the journal Nature, offers new information about the hazard potential of large earthquakes at subduction zones, where tectonic plates converge.

The magnitude 9 quake, which triggered a major tsunami that caused widespread destruction along the coastline of Japan, including the Fukushima nuclear plant disaster, was atypical in that it created an unusually large seismic movement, or slip, of 50 meters (164 feet) within a relatively small rupture area along the earthquake fault.

To better understand what may have caused this large movement, Scripps researchers used gravity and topography data to produce a detailed map of the geological architecture of the seafloor offshore of Japan. The map showed that the median tectonic line, which separates two distinct rock formations—volcanic rocks on one side and metamorphic rocks on the other—extends along the seafloor offshore.

The region over the earthquake-generating portion of the plate boundary off Japan is characterized by variations in water depth and steep topographic gradients of about six kilometers (3.7 miles). These gradients, according to the researchers, can hide smaller variations in the topography and gravity fields that may be associated with geological structure changes of the overriding Japan and subducting Pacific plates.

“The new method we developed has enabled us to consider how changes in the composition of Japan’s seafloor crust along the plate-boundary influences the earthquake cycle,” said Dan Bassett, a postdoctoral researcher at Scripps and lead author of the study.

The researchers suggest that a large amount of stress built up along the north, volcanic rock side of the median tectonic line resulting in the earthquake’s large movement. The plates on the south side of the line do not build up as much stress, and large earthquakes have not occurred there.

“There’s a dramatic change in the geology that parallels the earthquake cycle,” said Scripps geophysicist David Sandwell, a co-author of the study. “By looking at the structures of overriding plates, we can better understand how big the next one will be.”

Yuri Fialko, a professor in the Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics at Scripps and Anthony B. Watts from the University of Oxford are also co-authors on the study.