Washington, DC - Thursday morning Bloomberg released a report that detailed how Chinese spies had been inserting microchips no bigger than the size of rice on to SuperMicro motherboards. At least 30 companies and organizations that use those motherboards were affected. In many ways this epic failure in supply chain security feels like something out of a spy movie.

Suffice it to say this is a big deal.

There are myriad questions this incident raises: How will the US government view this provocation? What and how much data was compromised? Should other companies be worried about the potential for sabotage if they outsource any part of they supply chain to China?

And while I could give you my opinion on any one of those, I’d be a little out of my depth so instead I’m going to focus on one takeaway that I do know about: supply chain security has never been more important.

So, let’s do a quick rundown of the Chinese Spy Chip Scandal and then talk a little bit about supply chain security.

What happened with China and the tiny microchips?

Yesterday Bloomberg dropped a major report on how Chinese spies were planting tiny microchips on the motherboards of servers made in SuperMicro’s Chinese production facility.

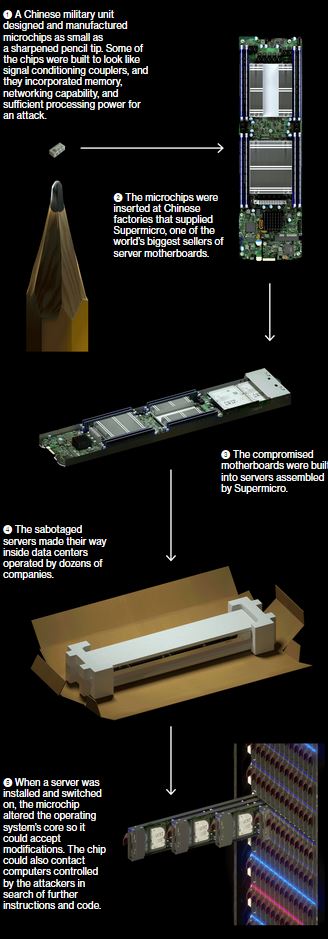

The chips had been inserted during the manufacturing process, two officials say, by operatives from a unit of the People’s Liberation Army. In Supermicro, China’s spies appear to have found a perfect conduit for what U.S. officials now describe as the most significant supply chain attack known to have been carried out against American companies.

As Bloomberg explains, there are generally two methods that intelligence agencies can use to alter the physical hardware of a device. The one favored by the US, which we know thanks to Edward Snowden, is called interdiction. It’s also a form of supply chain attack, but it focuses more on the logistics, intercepting the hardware at some point en route to one destination or another so that it can modify it and then let it continue along its way.

China doesn’t have to do that, owing to the fact that so many of the devices they would potentially want to modify are manufactured within its borders: 75% of the world’s mobile devices and 90% of its computers. This kind of supply chain attack is called a seeding attack, and up until this point it seemed like more of a hypothetical than something that could be done with any practicality.

Obviously, Bloomberg’s report would indicate that line of thinking was wrong.

This came to light because Amazon was considering the acquisition of a company called Elemental that sold video compression services. The motherboards that Elemental servers used were made by a San Diego-based company called SuperMicro, that had its production facility in China where the seeding attack took place.

During the ensuing top-secret probe, which remains open more than three years later, investigators determined that the chips allowed the attackers to create a stealth doorway into any network that included the altered machines. Multiple people familiar with the matter say investigators found that the chips had been inserted at factories run by manufacturing subcontractors in China.

This attack was something graver than the software-based incidents the world has grown accustomed to seeing. Hardware hacks are more difficult to pull off and potentially more devastating, promising the kind of long-term, stealth access that spy agencies are willing to invest millions of dollars and many years to get.

Already today, Apple and Facebook have admitted that they were targeted, though Apple did initially issue a denial. And I’m sure over the coming days and weeks this story is going to continue to develop.

Here’s a visualization of how the hack worked, as provided by Bloomberg

What does this say about supply chain security?

Let’s start with what our working definition for supply chain security is going to be. What occurs with actual hardware modification is exceedingly rare and kind of the nuclear level disaster of supply chain attacks. What we tend to refer to (at The SSL Store) with regard to supply chain security is more along the lines of cybersecurity.

But before we get into that, the biggest takeaway from this should be how one mistake, anywhere on your supply line, can be catastrophic. We’ve written about it plenty of times here because we spent so much time covering GDPR compliance, but having the best cybersecurity implementations in the world can be rendered entirely moot if one of your partners drops the ball. That’s why the GDPR requires data processing agreements and companies are supposed to audit their partners’ security.

But I’d also be remiss if I didn’t point out that no amount of planning could have probably anticipated state-sponsored sabotage.

Despite that, this is still a good time to go over some supply chain cybersecurity best practices. So here goes:

Supply Chain Security Best Practices

According to the US National Institute for Standard and Technology, you should construct your supply chain cybersecurity plan around three principles:

- Assume you will be breached. Start from the premise that a breach is inevitable.

- Understand cybersecurity isn’t just a technology problem, it’s a people and processes problem, too.

- Don’t divorce physical security from cybersecurity—security is security.

Now, before you can start getting into specific security implementations you’re going to need to perform a risk assessment. We’re not going to go too in-depth on that topic today (if you want to take a deep-dive I suggest you read the article), but the general idea is that you need to start by categorizing the types of risk you’ll face and their severity. And then start to look at strategies that will mitigate attacks and minimize risks.

Some of the concerns you’ll have from a supply chain standpoint will be third-party vendors or service providers with physical or virtual access to your company. Or security issues or lack of security from your partners. Or potentially purchasing hardware or software that is already compromised. And then there are software vulnerabilities in supply chain management or supply lines and even concerns about third-party data storage and data aggregators.

Ok, so let’s get into some actual examples of Supply Chain Cybersecurity Best Practices:

- Make sure that you include security requirements in every RFP and Contract. This is something you should already be doing if you are subject to GDPR.

- Depending on your size, sometimes when a new partner is accepted into the supply chain you should have a security team go audit them and assist with any updates and tweaks to their implementations.

- No second chances when it comes to delivering products that either don’t meet specification or are counterfeit.

- Make sure that any component purchases are being tightly controlled. And any part purchased from another vendor should be inspected and x-rayed before approval.

- All employees should undergo security training. Statistics show that employees are often the greatest threat to any organization’s security. Education is the best weapon against that.

- Obtain source code for all purchased software.

- Both hardware and software should make use of authentication, systems should not boot without requisite authentication.

- Automation, of all kinds from digital certificate issuance on up to manufacturing lines helps to minimize risk by reducing the amount of human intervention required.

- Use tracking programs that can map every component, part and system back to its origin point.

- Encrypt everything. Nothing should be sent or stored in plaintext. Encrypt data in transit with SSL/TLS and encrypt any data stored in physical databases or the cloud.